VRC V5 2023-2024 Over Under

June 2023 - May 2024

Roles: Team Lead, Designer, Builder & Coder

As a leading member of our robotics team, I participated in designing, building and coding our competition robots.

I also led the rest of our teammates throughout the year, with us as a team participating in competition such as Speedway, RiverBots, and Kalahari as well as our regional, provincial and international level competitions.

Competition Background

VRC “Over Under”

.png)

Our overarching goals included:

-

Robot Performance: Develop a robot with a 6-motor drivetrain for fast maneuvering, a reliable endgame hang (able to hang diagonally on poles/side bars to avoid defense), an efficient intake (to push triballs over barriers and de-score opponents’ balls), and a precise kicker (for consistent matchloading and scoring).

-

Autonomous Capabilities: Integrate odometry and PID control to improve autonomous skills accuracy, reduce error in movement, and ensure we could complete tasks like touching the elevation bar or scoring triballs without human input.

-

Mechanical Reliability: Optimize components such as strengthening drivetrain sleds, redesigning wings to be legal and retractable, and creating three hang mechanisms (pushdown, pullup, passive) for backup.

Throughout the project, we faced several critical hurdles that guided our problem-solving:

-

Mechanical Flaws: Gen 2 drivetrain sleds failed to cross ramps; the hanging mechanism’s six-bar arm had excessive “slop” (movement); the catapult struggled with triball placement and rubber band shearing; and the wings were concave.

-

Control & Coding Issues: The 360 RPM drivetrain made slow movements difficult; we had too few accessible buttons for tank drive; and autonomous code was under-tested.

-

Component Efficiency: The initial flywheel used a 1:6 gear ratio (too fast for control), and its exposed motor risked damage; the vertical kicker caused unpredictable ball bounces and backspins, complicating autonomous routes.

Research

To inform our designs, we focused on learning from existing solutions and real-world tests:

-

Reverse-engineered a kicker prototype to identify flaws and explore improvements like double slip gears to reduce wait time.

-

Studied technical resources: We used the PiLons Introduction to Position Tracking document to design odometry.

-

Drew inspiration from external innovations: For the sideways kicker, we referenced Mark Rober’s rock-spinning robot to solve the vertical kicker’s ball bounce issue.

-

Conducted post-match research: Analyzed performance data from events like Mall of America and Speedway Signatureto identify gaps, we learned matchloading was critical for winning, so we prioritized optimizing it.

-

Mentored other teams: Working with the University of Toronto Schools and Thornhill Secondary allowed us to test ideas and gain feedback on mechanical reliability.

Brainstorming

We held regular team discussions to evaluate options and pick the most feasible solutions:

Design Process

We iterated on designs to fix flaws and meet competition rules, with a focus on functionality and legality:

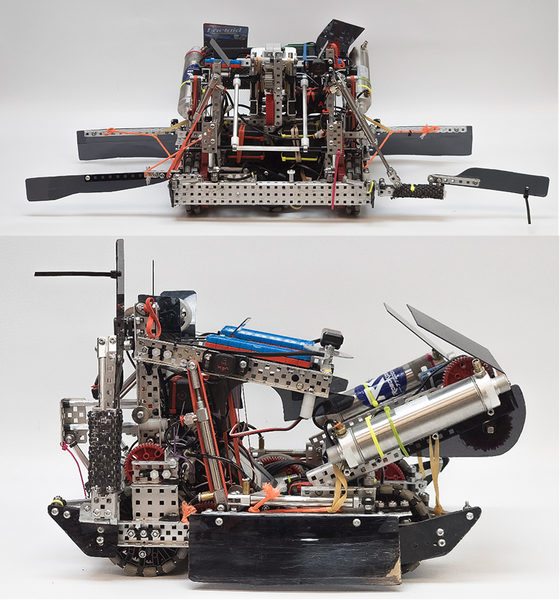

Drivetrain

Redesigned sleds from curved to straight angles, moved sleds from wings to the drivetrain, and strengthened them to cross ramps. For Gen 3, we added a 6-motor drivebase and adjusted weight distribution to prevent tipping.

Wings

Redesigned Gen 2 wings from concave to legal, switched from Lexan to metal, and removed the locking mechanism. For Gen 3, we made front/back wings lightweight and low-profile.

Hanging Mechanism

Strengthened the six-bar arm with banding to reduce slop, added a hinged stop bar, and designed a custom piston attachment for pushdown hangs. We also optimized pullup hangs with 4 pistons for speed.

Kicker

Designed a sideways kicker to create gyroscopic stability, reducing ball bounce and backspin. We also added a Lexan platform to auto-align triballs for consistent shots.

Intake

Hid the motor inside the intake to avoid damage, added foam wrapping to protect it from nets, and adjusted its height to prevent jamming when crossing barriers backward.

Coding Architecture

Designed an autonomous library with PID control, arc-tracking odometry (using distance sensors to correct error), and EMA filtering for smoother data.

Building Prototypes

Construction Focus:

Prioritizing the core functions, such as the drive base and scoring mechanism, to create a Minimum Viable Product (MVP) prototype.

VRC Prototype:

Building a prototype of the climbing mechanism and the drive system for barrier traversal, testing for load capacity and stability.

.png)

Coding Phase

The coding work focused on three core areas: driver control optimization, autonomous function development, and library integration—all tailored to enhance the robot’s responsiveness, accuracy, and reliability during matches. Below is a detailed breakdown of the key coding tasks and implementations:

Driver Control

The primary goal of driver control coding was to address the 360 RPM drivetrain’s high sensitivity (which caused overshooting during slow movements) and optimize button mapping for efficient operation without compromising control.

Joystick CurvesProblem Solved:

-

Directly scaling joystick inputs to motor voltages led to difficulties in precise, slow movements due to the drivetrain’s rapid acceleration. Differentiating between 25% and 50% joystick pushes was also challenging, increasing operational error.

-

Solution Implemented: An exponential joystick curve was adopted, which significantly reduced sensitivity for small joystick inputs while preserving full-throttle capability for maximum speed. A modified curve was additionally applied to turn inputs—this filtered the difference between left and right motor outputs using a custom formula to minimize erratic turns and prevent overshooting targets.

-

Rationale: This approach was chosen over two alternatives because it offered dynamic adjustability and intuitive control for drivers, unlike the inflexible “slow-set zone” or unresponsive slew rate.

Button Mapping:

-

Problem Solved: Tank drive only allowed access to 4 buttons without releasing the joysticks, but more than 5 functions were required for match operations.

-

Solution Implemented:

-

Three button input types were defined: Hold Buttons, Toggles and Macros

-

A “shift key” was mapped to one button, creating 6 unique button combinations. When unused, the shift key prioritized intake control; when pressed, it switched to wing toggles and arm macros.

-

Auton Library

The autonomous library was built to standardize and improve the robot’s autonomous movements, integrating key control theories to minimize error and ensure consistency—essential for qualifying for the World Championship via autonomous skills.

PID Controller:

-

Customization: The PID controller deviated from base code with tailored logic for task completion. It used a combination of proportional correction, integral correction, and derivative correction to adjust motor outputs.

-

Exit Condition Logic: Tasks were marked complete only after crossing the “error = 0” threshold a specified number of times. For quick, low-accuracy tasks, the robot terminated once it stalled or crossed the threshold once; for high-accuracy tasks, it crossed the threshold up to 4 times to eliminate residual error.

Motion Profiling & Odometry:

-

Arc-Tracking Odometry: To maintain accurate position tracking, an arc-tracking odometry system was implemented—derived from the PiLons Introduction to Position Tracking document with three key modifications.

-

Error Correction: Distance sensors (placed on 2-4 robot sides, unobstructed by triballs) updated the robot’s position vector by detecting field walls. Four filters prevented invalid updates.

Additional Integrations:

-

EMA Filtering: Exponential Moving Average (EMA) filtering was added to smooth sensor and encoder data, reducing signal noise that could disrupt autonomous movements.

-

Feedforward Control: Incorporated into motion logic to anticipate motor output needs, improving response speed and reducing PID correction load.

Autonomous

Autonomous coding focused on translating the library’s capabilities into match-ready tasks, with iterative improvements based on post-event analysis to fix gaps and boost performance.

Key Task Implementations:

-

Directly scaling joystick inputs to motor voltages led to difficulties in precise, slow movements due to the drivetrain’s rapid acceleration. Differentiating between 25% and 50% joystick pushes was also challenging, increasing operational error.

-

Solution Implemented: An exponential joystick curve was adopted, which significantly reduced sensitivity for small joystick inputs while preserving full-throttle capability for maximum speed. A modified curve was additionally applied to turn inputs—this filtered the difference between left and right motor outputs using a custom formula to minimize erratic turns and prevent overshooting targets.

-

Rationale: This approach was chosen over two alternatives because it offered dynamic adjustability and intuitive control for drivers, unlike the inflexible “slow-set zone” or unresponsive slew rate.

Post-Event Iterations:

-

Mall of America: After autonomous tasks failed to complete consistently, code was adjusted to start routines earlier and include more pre-match field testing.

-

Speedway Signature: Autonomous under-testing led to incomplete tasks; additional testing protocols were coded to validate routines before matches.

-

RiverBots II: Fixed intake drop issues in autonomous routes and tuned paths to align with the new sideways kicker’s grouping—resulting in a decent 160-point skills score and only 3 autonomous win point (AWP) mistakes.

Achievements

Our phased work paid off in both technical improvements and competition results:

-

Mechanical Wins: Gen 3’s 6-motor drivetrain crossed barriers smoothly; the sideways kicker reduced ball spread (we loaded 44 triballs in 20 seconds); the final wings were legal, retractable, and pushed triballs effectively; and the three hang mechanisms allowed us to achieve the “highest hang” at Speedway Signature.

-

Coding Success: The joystick curve fixed overshooting, and the autonomous library improved skills accuracy—we only messed up 3 autonomous win points (AWP) at RiverBots II. We also simplified button mapping, allowing drivers to reach 200 points in teleop skills.

-

Competition Results: At RiverBots II (Dec 2023), we ranked 16th in qualifications and beat the 2nd seed; at Speedway Signature (Nov 2023), our alliance strategy won matches and we secured a top-3 partner. We also made progress toward World Championship qualification by optimizing autonomous skills.

-

Team & Mentoring Impact: We mentored two robotics teams (growing their skills) and strengthened our team via activities like go-karting and escape rooms—improving collaboration during matches.

This project taught us the value of iteration: every flaw (e.g., concave wings, sensitive joysticks) became an opportunity to refine our design, and every post-match analysis helped us align better with competition goals. In the end, our robot was not just a machine—it was a product of teamwork, research, and relentless testing.